THE A.V.G. ENDS ITS FAMOUS CAREER

by CLARE BOOTHE LUCE

-- Life Magazine July 20, 1942 --

On July 4 the A.V.G. was inducted into the U. S. Air Forces in China and India. What was the A.V.G.? How did it get to China? And what did it prove? It mathematically proved in six long and terrible months of sky battling that man for man and plane for plane the American is exactly five times better in combat than the Japanese today.

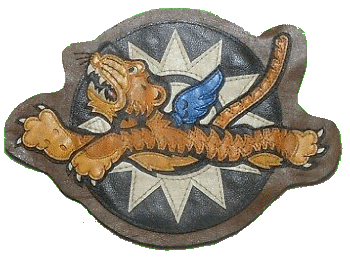

In the autumn and early winter of 1941, there were too young American pursuit pilots stationed at Toungoo, Burma. They wore the uniform of the Chinese Air Force. Their directive from Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek was, upon the completion of their training under Brigadier General Claire L. Chennault, to protect China's lifeline, the Burma Road. Madame Chiang Kai-shek smilingly called them "my angels with--or without--wings." More prosaically they called themselves the American Volunteer Group. They had painted the noses of their 54 Chinese-owned Tomahawks (P-40's) to resemble the snouts of ravenous tiger sharks. (The Japanese, a fisher folk, have a horror of sharks. All America called them the "Flying Tigers" now. They were, although this is a matter of no significance, nearly all blond and more than half of them were 6 ft. tall. They hailed from 39 of the 48 States of the Union. The names of their home towns made music such as Walt Whitman sang and Carl Sandburg sings now: Waseca, Coronado, Red Level, Marshall, Otis, Yamhill, Scarsdale, Seattle, Savannah, Middletown, Plymouth, Randalia, Minneapolis, Boise and San Antonio.

Many of them were pilots who had resigned from the U. S. Air Forces of the Navy, Army and Marine Corps to "sign on" as employees of Camco (Central Aircraft Manufacturing Co.). This was an American concern which had been making planes for the Chinese Government in its factory at Loiwing, China. The Chinese Government had an agreement, in turn, with Camco to take over not only its planes for the defense of China but also to take the new "employees" into its depleted Army Air Force when they arrived. They say in the Army now that a thousand or more other American lads yearned to go but there were neither the planes for a thousand pilots in Chungking nor the plans in Washington in those days.

When they flew from the U. S. to Burma, each of these young men had a year's contract with Cameo in his pocket. It guaranteed him his transportation to and from China, a salary of $600 to $750 a month, a bonus of $500 for every, Japanese plane destroyed in the air and the right, which they all demanded because they all cherished it above any other, to cancel that contract in the event that their America should find itself at war with Germany or Japan, in order to return to fight in their respective services, the Army, the Navy, the Marine Corps. Strictly speaking, they were "mercenaries of the air." So they set forth on their voyage across the troubled Pacific whimsically disguised as tourists, acrobats, missionaries, students, businessmen, artists. (But in a sense, all of these things were what they were.)

For a congeries of motives carried them to Burma: a little money to buy

their girls pretty rings, or the folks a car, to marry on, or just to

laugh and play on; a burning belief in China's cause; the love of high

adventure in an alien land; or the sheer thrill of air combat. Each of

them knew when he left his own peaceful land he might face a winged doom

in the skies of Cathay. Like Yeats' Irish Airman fighting for England,

each volunteer could have said:

I know that I shall meet my fate

Somewhere among the clouds above;

Those that I fight I do not hate,

Those that I guard I do not love. . . .

Their commander, General Claire Chennault of Water Proof, La., was a former American Army air colonel, a World War I pilot, a onetime daredevil barnstorming stunt pilot and an expert on aerial tactics. Asked what he looked like, an A.V.G. pilot said, "Well, his face kind of looks like he'd been holding it over the side of a cockpit into a storm for years." Chennault, who had been serving in China's Air Force for several years before the A.V.G. boys arrived, had long been pondering the technique of the Japs and preaching many new techniques of his own for pursuit in air combat. In these American youngsters Chennault found the disciples of his heart's desire. (Every one, he claimed, would go home capable of being a squadron leader.) From the day they landed in Burma, everlasting teamwork, discipline, precision flying, split-second formation attack in twos and threes filled their flying hours. First outthink, then outfight the enemy. For dogfights, he substituted formation assaults. Not do or die alone but do together and don't die was his motto. Nevertheless, during this training period while he was shaking his Army, Navy and Marine lads down into a combat team and waiting impatiently for planes, spare parts and ammunition, Chennault used to say rather wistfully, "There is no training substitute for being shot at."

The shooting began rather earlier than Chennault and his 100 boys with their 54 obsolescent planes had bargained for. But the account which the A.V.G. then proceeded to give of itself justified not only Chennault's untried gospel of the flying team but America's untried faith in her sons of the sky. "We raised all hell on a shoestring," said one A.V.G. boy.

From Dec. 7 until the Flying Tigers were inducted into the American Army under U. S. General Brereton, they had for all their operations not more than 100 pursuit planes, including replacements, and there was a desperate shortage of spare parts. Never more than 50 planes were in commission at once nor more than 18 planes, or a squadron, in the air at any one time. And yet, by July 4 the Flying Tigers had destroyed 115 enemy planes on the ground, 171 enemy planes in the air--while Camco gleefully jingled its till to the tune of $136,000 in bonuses. Thus, 497 Japanese planes fell through Burma's skies in flames or burst in flames on Burma's ground before the guns of the Yanks from 39 States of America. And at what cost to the Flying Tigers? Four former Army pilots killed in action, eight former Navy pilots killed in action, one former U.S. Marine pilot killed in action. Four hundred ninety-seven Japanese planes at the cost of 13 American boys! The figures sing as no words can: 34 Japanese planes for every P-40 destroyed; 97 Japanese airmen killed for every American boy.

When Rangoon was falling, Chennault pulled out the A.V.G. from Mingaladon Field back to Magwe. That is, he pulled it all out but 18 pilots, 18 planes. On Christmas Day, in the morning, 60 Japanese bombers escorted by 18 fighters converged on Rangoon. Up from the field zoomed the lone Tiger Squadron, each pilot's eyes glancing alternately from the instrument board, which is then the Face of God, to the devilish quarry thick in the air around. "It looked," said a witness on the ground, "like a few little rowboats attacking the Spanish Armada. "And down came nine Japanese bombers, eleven Japanese fighters. The Flying Tigers lost no pilots, damaged one plane. This established the battle ratio and tempo that held good all through the blazing days of the Battle for Burms.

"We can take the Japs on one-to-five," the Flying Tigers boasted and made the boast good. The planes they flew may not have been as good as the Japanese Zero fighters, which mounted faster and turned faster. But an A.V.G. officer said, "These kids don't care about that. They just go ahead and outfight those bastards. You could give them wheelbarrows and I think they'd still fly."

And though the Philippines were falling, Singapore was gone and the Indies were doomed and Burma was threatened, although the enemy seemed to be everywhere in those days and everywhere seemed to be unbeatable, America was not afraid. A hundred American volunteers had taken the measure of the enemy. Who, in the face of that measure, dared doubt that America could if it would defeat Japan? The Flying Tigers were a blazing beacon of ultimate victory. For this happy revelation of theirs in our darkest hours their story is deathless. And deathless too is our gratitude.